SETI

Tuesday 18th May, 2021

|

Our speaker (on Zoom) was Dr Mike Leggett who talked to us about "SETI" which is short for the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. He has a background in chemistry and biology but has been working in programme management and standards. He is the General Secretary of the Society for the History of Astronomy as well as being the Vice Chair of Milton Keynes Astronomical Society and regularly produces their handbook.

Dr Leggett said that the search for life in the Universe can in some ways be described as looking for the proverbial needle in a haystack. This is summed up quite well by the quote from the late Douglas Adams' book "The Hitchhikers' Guide to the Galaxy" which says: ""Space is big. Really big. You just won't believe how vastly hugely mind-bogglingly big it is. I mean, you may think it's a long way down the road to the chemist, but that's just peanuts to space".

The search began in earnest in the early 1900s after radio waves were studied by the German physicist Heinrich Hertz in 1886. The Inventor and engineer Guglielmo Marconi then used Hertz's work to develop long-distance radio transmission which earned him a share of the 1909 Nobel Prize in Physics. In fact the futurist and inventor, Nikola Tesla may have picked up some of Marconi's early tests and thought they may have come from a civilisation on Mars as they ended when Mars set below the horizon.

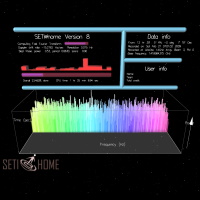

The modern era of SETI began in 1959 with an article in the scientific journal Nature which explained the potential of using microwave frequencies to communicate between star systems. It was realised early on that radio waves travel relatively unimpeded through the vast distance of space unlike other wavelengths. Around the same time a radio astronomer, Frank Drake, had also come to this conclusion and so, in the spring of 1960 there was the first microwave radio search looking for any signals from beyond the Earth.

Drake pointed a radio antenna in West Virginia, USA, at two nearby stars that resembled our Sun. His experiment called "Project Ozma" involved tuning the antenna (just as you tune your small radio to an Earth-based radio station) to look for signals with a wavelength of 21 cm. This wavelength was chosen as, not only would it pass easily across vast distances of interstellar space, but it would not be absorbed by all the water vapour in Earth's atmosphere. Sadly, the project failed to detect anything, but it prompted Russian astronomers to do wide sweeps of the sky to look for signals.

In 1961 Frank Drake came up with an equation (now known as the Drake Equation) to try and quantify the number of civilisations in the Milky Way that might be able to communicate with us. It consisted of a number of terms multiplied together. It essentially tries to work out what fraction of planets around distant stars actually go on to host intelligent life, and would go on to produce technology able to communicate over vast distances of space. However, many of the factors in the equation are very difficult to estimate and so it has not helped in narrowing down the search.

The latest search, Breakthrough Listen, is a well-funded project using thousands of hours of telescope time, and so is the most comprehensive to date. It began in 2016 and will run for another 10 years, targeting one million nearby stars and the centres of 100 galaxies. This search will be able to cover ten times more of the sky than previous searches, covering frequencies in the 1 to 10 Gigahertz range, which is a radio "quiet zone" where radio waves are not blocked by cosmic sources or the Earth's atmosphere.