Cracking an Interstellar Mystery

Tuesday 21st January, 2020

|

Our speaker was Dr Michael McCabe who came to talk to us about "Cracking an interstellar mystery". He is retired now but used to work at Portsmouth University in the Department of Mathematics. He explained that the mystery referred to in the title of his talk relates to a phenomenon called "diffuse interstellar bands".

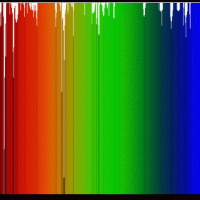

He continued by saying that starlight from a distant star can be split into a sliding scale of colours - from purple to blue, then through green and yellow, then orange, and finally red at the other end; very similar to a rainbow. If the starlight travels through some material on its journey to us then small sections of the colours are absorbed by the material. In other words, certain wavelengths of the starlight are blocked by the intervening material, This leads to gaps appearing in the spectrum of colours. These gaps are known as bands, and they are described as "diffuse" as the edges of the gaps are somewhat blurry, and the adjective "interstellar" is used as the matter blocking the starlight is located between the stars in our galaxy (the Milky Way) or even outside our own galaxy.

To date, around five hundred diffuse interstellar bands (or DIBs) have been discovered and these are seen at ultraviolet, visible and infrared wavelengths of light. The origin of any of the DIBs was unknown until July 2015 when scientists from the University of Basel announced that two of the bands were due to starlight being absorbed by a carbon molecule called Buckminsterfullerene.

This molecule, with the chemical formula C60, consists of sixty carbon atoms arranged in the shape of a football and is sometimes called a "buckyball". These large carbon molecules probably originate from giant red stars known as carbon stars that expel their carbon atmospheres into space as they age.

Dr McCabe said that DIBs were first observed by a female American astronomer called Mary Lea Heger. She was studying for her doctorate at the Lick Observatory in 1919 and was examining the stars beta Scorpii and delta Orionis, amongst others. To analyse the starlight from all these stars she used the Lick's 36-inch refractor telescope and glass photographic plates to capture their starlight split into a spectrum of colours. On the plates she noticed two definite bands that were not the result of starlight being absorbed by a star but she thought by some sort of sodium cloud that sat in the space between the star and Earth.

Dr McCabe concluded his talk by saying that, currently, only 5 bands (out of the 500 known DIBs) have been identified as resulting from the presence of certain molecules in interstellar space. He hopes that a new survey programme named EDIBLES, using an instrument known as a spectrograph on the Very Large Telescope in Chile will discover new molecules that cause these gaps in a star's spectrum.

This article was written for the club news column of the Stratford Herald. The actual lecture explained the subject at a deeper level.